The magic of the masks

Festival Muro Crítico. Arroyomolinos de la Vera, Cáceres, Spain.

2024

I was invited to participate in the festival doing a mural in homage to the rite of the “Mascarones”, an ancestral rite of passage that is still alive in this small town in the north of the province of Cáceres. For me it was an honor to be able to contribute with my work to the conservation and strengthening of such a valuable event as this. At the same time the muralists Brea and Jaiku painted in the same village other walls with amazing art pieces.

Mural painting intervention for the Mural Festival “Muro Crítico” curated by Sojo, funded by the Diputación de Cáceres.

The “Mascarones”, a word derived from Mask, is an ancestral ritual linked to the Winter Solstice in which a great part of the town's neighbors, men and women, young, children and elders, participate. It is something deeply rooted in their identity, in the identity of the village itself. It consists of running around the village in groups dressed in costumes made with burlap sacks from the cultivation of tobacco (very common in this region), a mask made with a black or white cloth, a straw hat from working in the fields and cowbells or “campanillos” as they call them there tied to the waist that ring fervently when running and jumping. Formerly they entered the houses to make what was called the “cuestación” which is to ask for some food, such as “chorizo” or other pork sausages, which accompanied with large quantities of wine, they also made practical jokes like throwing salt into the fire of the fireplace to make a flare. According to some testimonies that I received from neighbors, some of them took advantage of the situation to take revenge for some personal matter, since they were masked and could not be recognized. The cowbells were tied behind so that they could not be seen, since in the town they all knew each other so well that they could recognize the person by his cowbells, some could even recognize them by the sound they made.

The neighbors told me that during the fascist dictatorship these celebrations were forbidden but they still continued celebrating. As the village was located on a hill, the children watched the road from the big rocks and warned if the Civil Guard came (police). On one occasion someone was arrested for celebrating the ritual. Formerly they did not carry a torch, they used to do it during the day, but in recent years, after creating a cultural association for the organization of the ritual, they added the torches and to do it at night, to give it a more magical and attractive aspect.

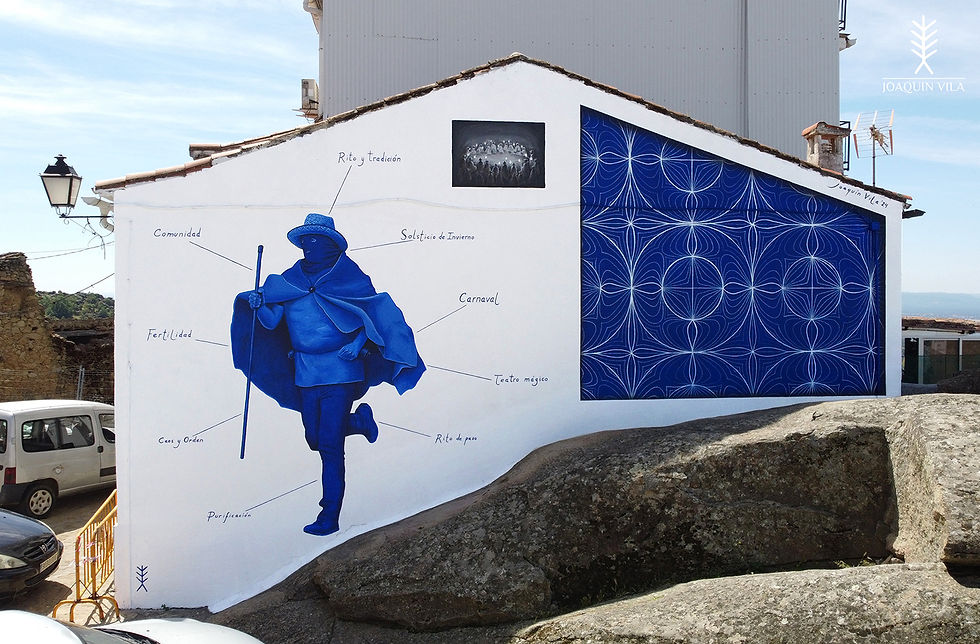

The place where the mural is, in the viewpoint, is where all the “Mascarones” gather in a great circle to sound their cowbells. The mural represents in its left part, “What we see in the Ritual”, a “Mascarón” running, taking inspiration from the scientific illustrations several parts of the body and the costume of this one are indicated, but in the description what we can see are words that make reference to the Ritual itself, more than to the own costume. Since I did not have a real photo of a “Mascarón” running in the posture I was looking for, I asked a neighbor to lend me her son's costume and Sojo, the curator, put it on him to take the photo in the posture I was looking for. On the upper part of the mural is painted a photograph of all the “Mascarones” in a circle with the torches, taken in the same location where the mural is located years before. On the right side we see “What really happens”, a large surface with a drawn pattern, which alludes to the movement of energy, of the invisible fabric that connects all living things, that fabric that is modified and interacts when the entire village enters into communion to perform the ritual and invoke the forces of life.

The pure sense of these rituals has several parts:

1. To purify and energetically cleanse the village, driving away evil spirits, through the sound with the cowbells.

2. To invoke the forces of life, awaken mother earth and attract fertility for people, animals and plants.

3. Ritual of passage: originally this was the moment in which the young people who turned 15 years old that year celebrated their passage to adulthood and the whole village celebrated and welcomed them. It was the young people who wore the costumes and were in charge of representing the ritual and organizing the party. Nowadays, due to the lack of young people in the villages, all the people of any age who want to participate, stage it. They can reach about 50 people.

4. Moment of communion and catharsis. These rituals are something that unifies the people, that weaves the identity of the community, that is beyond politics and religion. All the people participate in one way or another, which makes them unite and reaffirm themselves as members of the same community. They dance, drink, have fun, celebrate life, discharge energy and thus renew life, marking a before and after in the year.

5. Sun: The meaning of these rituals in winter is that the winter solstice is celebrated, the moment in which the sun reaches its southernmost point, and the days become longer again. It is the day of the rebirth of the Sun, the 25th of December, the moment in which symbolically the Light wins back the darkness, and the days become longer again. It is the true beginning of the year. Moment of celebration of a cycle of eternal return as Mircea Eliade said, a milestone in the annual calendar, which helps us to be aware of the cycles and reassures us to know that everything returns to its place, gives stability.

The Winter Masquerades, as this type of rituals are known in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal), are very widespread rituals throughout Europe, which are lost in the origin of time. All of them coincide in the symbolism and the intention of the ritual, varying the costumes and the forms of representation. We can find them in Romania, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Portugal, Lithuania, England, Italy and many others.

Keeping these rituals alive makes us keep the link with the natural cycles and in that way we can be more in tune with Nature, value and respect it. It gives us an order, a cyclical balance, a more harmonic structure to live in and a more natural way.

I want to thank Sojo, the curator of the festival, for the invitation and trust, for his dedication and his good work as a curator. Also to all the people of Arroyomolinos de la Vera for their warm welcome and sympathy.